For many years, Kenyan courts and prisons have witnessed a dreary procession of citizens with broken limbs and bruised bodies. A majority of them did not deserve the violence meted out on them during their arrests and subsequent incarceration. A great many cases did not register any complaints. In cases where complaints were raised, charges were generally dismissed. The police have been practically above the law.

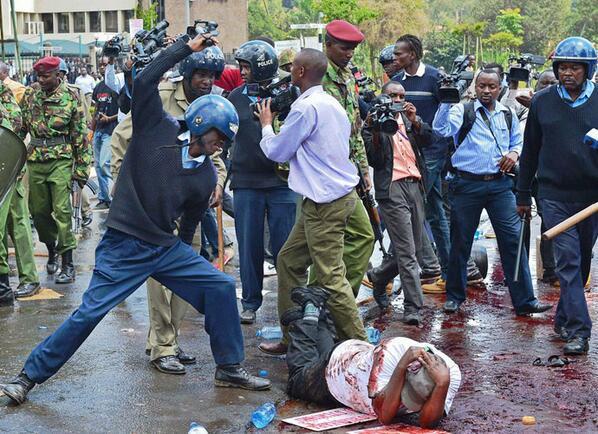

Clearly, images of police brutality and mistreatment of citizens have a precedent in Kenyan history. The issue of police brutality is rapidly gaining urgency in practically every region that has reported some sort of strife, deep hostility between police and the masses has been one of the primary causes of the riots.

Whether or not the police accept the words “police brutality”, the public now wants some plain answers to plain questions. How widespread is police mistreatment of citizens? Is it on the rise? Why do the police mistreat citizens? Do the police mistreat poor Kenyans more than the well -off Kenyans?

Obtaining information about police mistreatment of citizens is no simple matter. Various lobby groups and human rights bodies receive hundreds of complaints about mistreatment- but proving these allegations is difficult. Rarely do these complaints lead to the disciplining and dismissal of police officers for alleged brutality. Generally, police bosses keep silent on the matter or answer these charges with vague statements that they will investigate and complaints brought to their attention. Rank and file officers are usually more outspoken, insinuating that charges of brutality are part of a conspiracy against them, and against law and order.

What citizens mean by police brutality covers the full range of police practices. These practices are the ways in which the police have traditionally behaved in all sorts of civil disturbances. The most common of these practices are the use of abusive, profane language and the use of physical force, viewed in the eyes of the citizen as violence.

Citizens and police do not always agree on what constitutes proper police practice. What is “proper” or what is “brutal” is more a matter of judgment about what someone did than a description of what police do. What is important is not the practice itself but what it means to the citizens. What citizens object to and call “police brutality” is really the judgment that they have not been treated with the full rights and dignity owing citizens in a democratic society. Any practice that degrades their status that restricts their freedom that annoys or harasses them, or that uses physical force is frequently seen as unnecessary and unwarranted. More often than not, they are probably right.

Many police practices only serve to degrade the citizen’s sense of himself and his status. This is quite true with regard to the way the police use their language. Most citizens who have come into contact with the police object to the way police officers talk to them. Particularly objectionable is the habit police officers have of “talking down” to citizens, calling them names that deprecate them in their own eyes and those of others and of course the use of violence. Citizens want to be treated as people, not “non persons” who are subjected to physical and emotional abuse.

That many Kenyans believe that the police have degraded their status is abundantly clear. Many of them can attest to being talked down to. Others can attest to some sort of physical abuse from the officers.

To be treated as “suspicious” is not only degrading, it is also a form of harassment and a restriction on the right to move and interact freely. The harassing tactics of the police- dispersing social gathering among the youth, indiscriminate stopping of youth and commands to move on or go home are particular common in the poorer areas of Nairobi and other Kenyan cities and towns.

Young people are the most likely target of police practices that see them dispersed or arrested. Rampant unemployment and increased costs of living have led to youth from the poorer areas of our cities and towns spending lots of time in public places. Given the inadequacy of their housing and the absence of community facilities, the street corner or the local wines and spirits outlet is their social center. Police on patrol regularly target such places.

Police harassment is not confined to the youth alone. Adults in places like Dandora, Umoja and Kayole can attest to being stopped and questioned by police on more than one occasion and without good reason. Others say they have been arrested for no particular reason and have ended up facing “trumped up” charges in a court of law. The lucky ones have managed to buy their freedom after parting with variable sums of money paid out to the police officers and their superiors.

What citizens regard as police brutality is viewed in the police force as necessary for law enforcement. While degrading epithets and abusive language may no longer be considered proper by police bosses and citizens, they often disagree about other practices related to law enforcement. For example, though many citizens see “stop and question,” “stop and search,” or “msakos” (swoops) as harassment, police bosses usually regard them merely as “aggressive prevention” to curb crime.

The hue and cry of police brutality seems to lie in police use of physical force. By law, the police have the right to use such force if necessary to make an arrest, to keep the peace, or to maintain public order. But just how much force is necessary?

This is a critical question that the Kenya Police will have to answer, especially in the wake of images of their officers dispersing riots in recent days. Sources within the police intimate that police officers should only use that amount of force they reasonably believe to be necessary. These sources further add that police officers are permitted to use deadly force in self defense.

This right to protect themselves often leads police officers to argue self defense whenever they use force. It is common knowledge that many police officers, whether or not the facts justify it, regularly follow their use of force with the charge that the citizen was assaulting a police officer or resisting arrest. It is an open secret that some police officers even carry weapons that they confiscated from other crime scenes and plant them at scenes should it be necessary to establish a case of self defense.

Of course, not all cases of force involve the use of unnecessary force. The police can use force where a citizen is resisting arrest and needs to be restrained and/or subdued. Sadly, it is common practice to see police officers continuing to use force even after the offender has already been subdued. This seems to be the culture within the police force even though official police practice does not condone such behaviour.

The police force is an organization that processes people. All people-processing organizations face certain common problems. But the police administrators face a problem in controlling practice with clients that is not common in most other organizations. The problem is that police contact with citizens occurs in the community, where direct supervision is not possible. Assuming our unwillingness to spend resources for almost one-to –one supervision, the problem for the police commissioner is to make sure police officers behave properly when they are not under direct supervision. The commissioner also faces the problem of making them behave properly within their units as well.

Historically, one way apart from supervision deals with this problem. That solution is professionalization of workers. Perhaps only through the professionalization of the police force can we hope to solve the problems of police malpractice and brutality.

But lest anyone optimistically assumes that professionalization will eliminate police malpractices altogether, we should keep in mind that problems of malpractice also occur regularly in other fields.